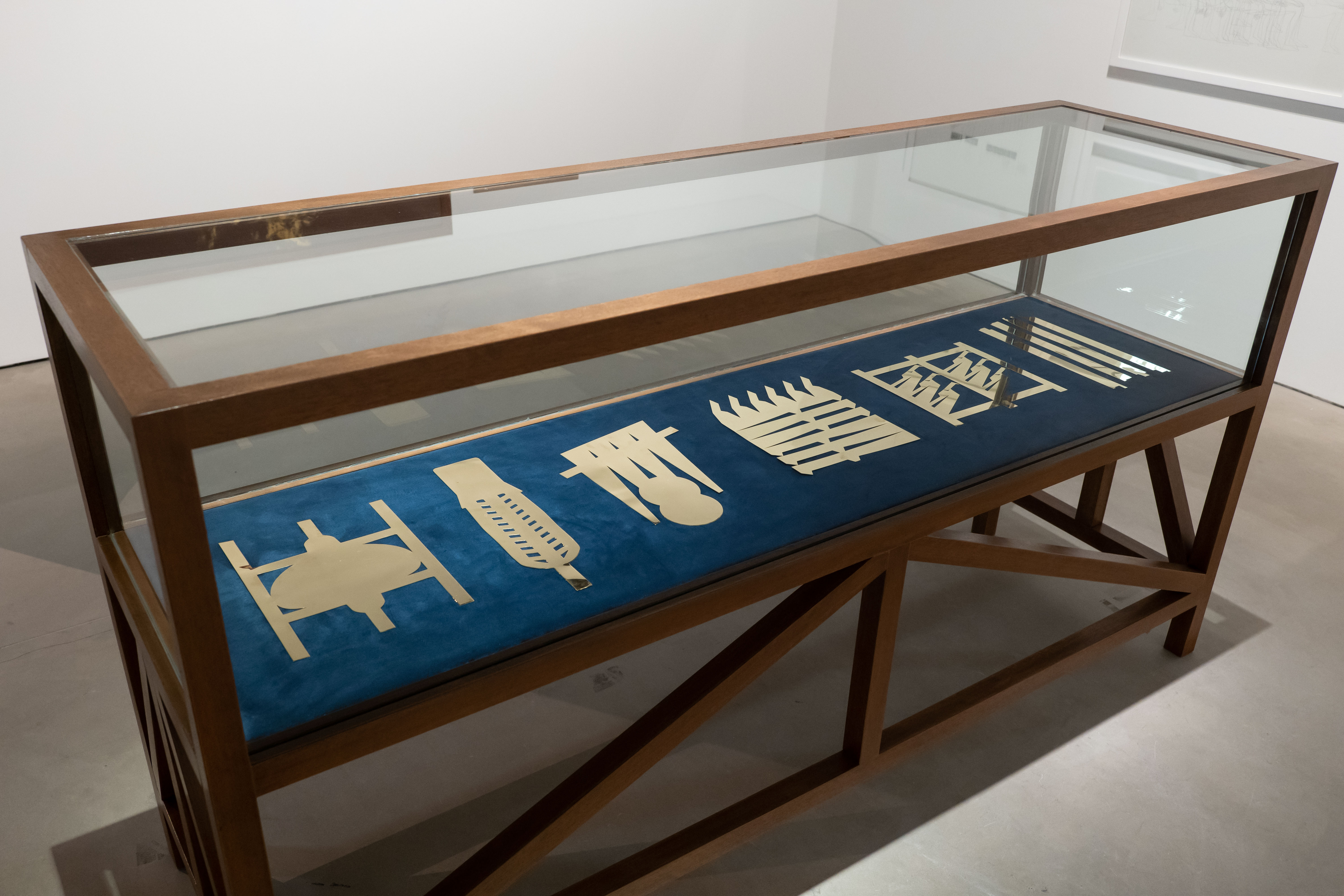

Semenkh-Ka Re: The Many Forms of Silence

Sculpture and drawing installation, 2022

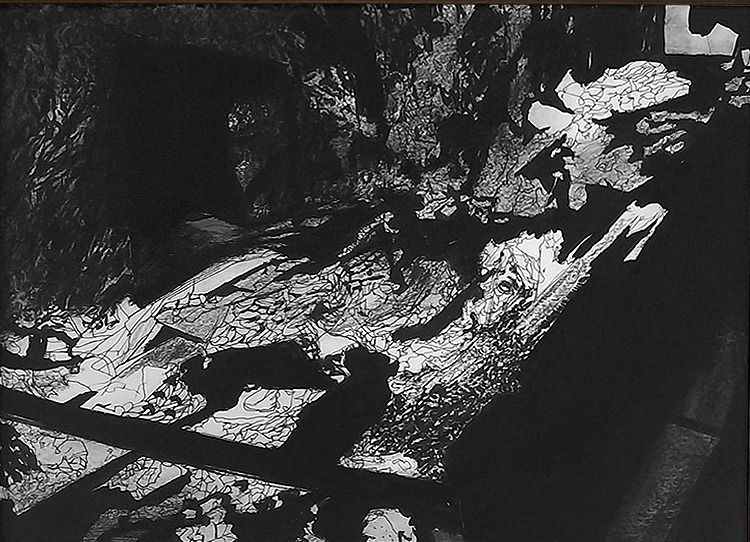

Semenkh-Ka Re: The Many Forms of Silence (MFS) is a drawing and sculpture installation inspired by two relics in the collection of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. In 2017, during a visit to the Egyptian Museum, Doa Aly came across the haunting debris of an excavation: two blocks of clay, approximately 35 x 25 cm each, with twisted bands of gold and fragments of stone (bone?) embedded in them. They were part of a jewelry display, surrounded by an array of gold trinkets. Behind them, photographic images of a contemporary archeological dig documented the careful disinterring of objects, it is not clear if the objects on display and the photographs are related. A wall label referred to the displayed items as “Jewels of King Semenkh-Ka Re,” excavated from a site that archeologists have designated Tomb 55 of the Valley of the Kings, or KV55. Since 2019, the objects have been removed from display and stored, awaiting a possible relocation to Cairo’s new Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM).

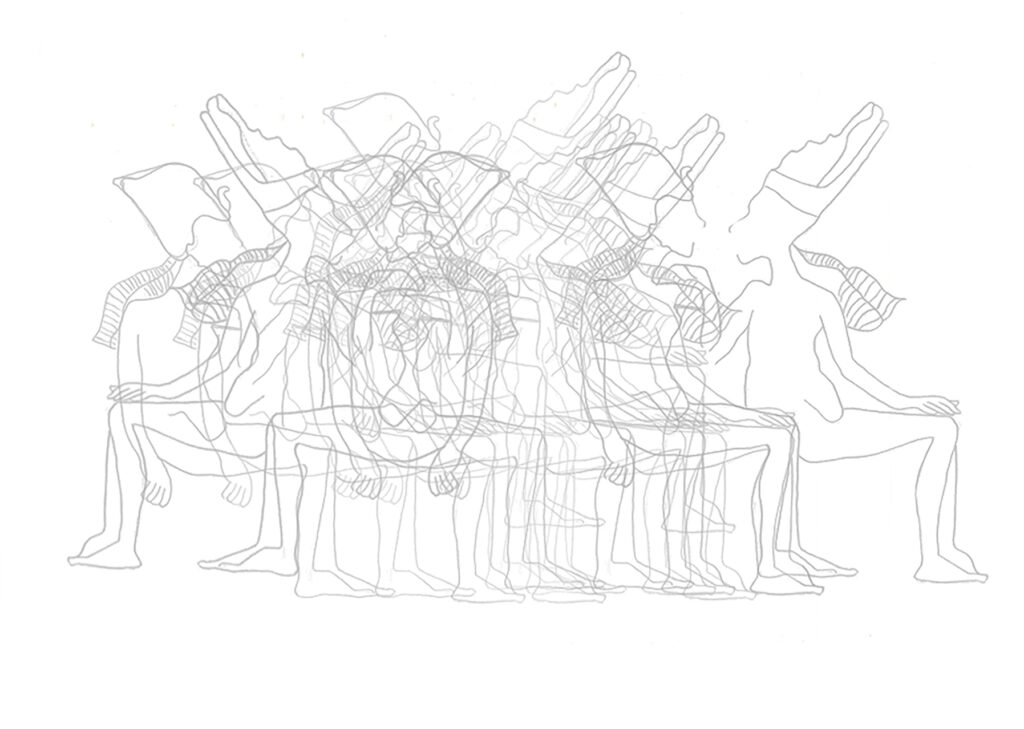

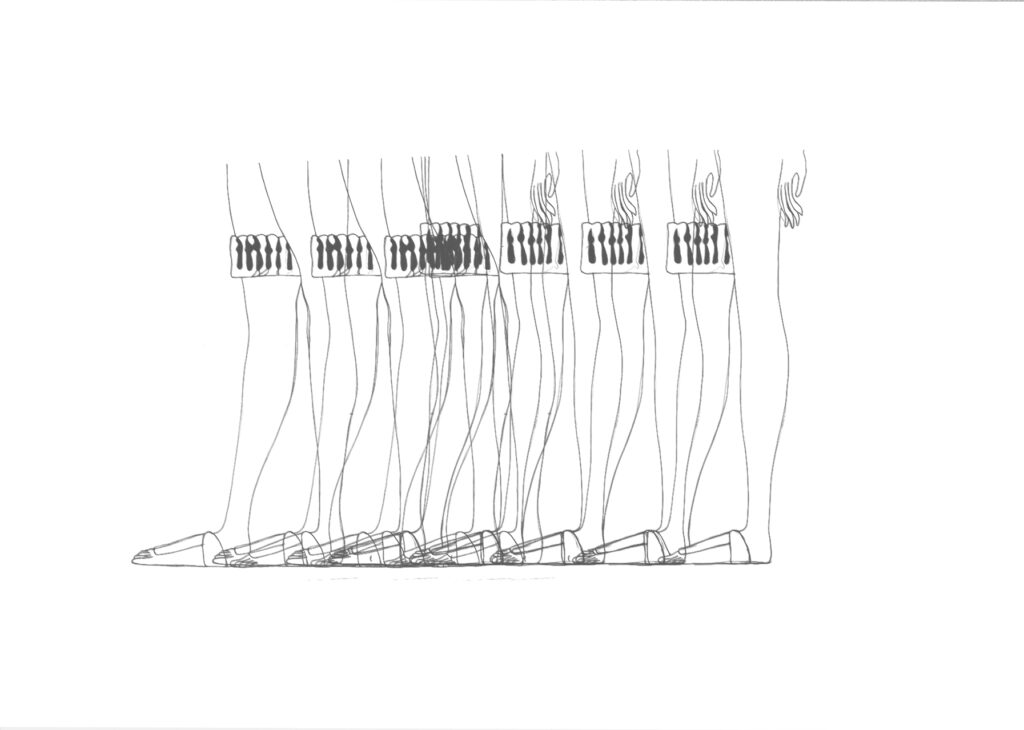

Trying to understand the nature of these objects led the artist to the controversial 1907 excavation of KV55, by American businessman Theodore Davis, as well as the ambiguous identity of King Smenkhkare, and the last turbulent years of Akhenaten reign. MFS is a study of forms, the tracing and erasing of forms, moving backwards from the obscurity of KV55 towards Akhenaten’s cities of silence.

Smenkh-Ka Re was commissioned by the 7th Singapore Biennial-Natasha, 2022, curated by Ala Younis, Nida Ghouse, June Yap, and Binna Choi.

KV55

In 1907, the New York businessman Theodore Davis, who had obtained a permit to excavate in the Egyptian Valley of the Kings, discovered a corridor and chamber which contained the various funerary objects possibly belonging to various individuals. He identified the site as the tomb of Queen Tiye, because her name was on a dismantled funerary shrine made for her by her son Akhenaten. He perpetuated this identification in his 1910 publication of the discovery, The Tomb of Queen Tiyi. The mouth of the tomb had been filled with stones and rubble upon which were lying two wooden doors of a shrine. The bottom of the shrine was inscribed with “Beloved of Waenre” (beloved of Akhenaten), which led archeologists to believe the shrine was made by Akhenaten for his mother.

The tomb’s chamber contained a partly collapsed wooden coffin, adorned with gold foil and glass, further sections of the shrine, and a niche with four canopic jars. Beside the coffin lay a mummy, badly damaged by damp with its arms reported as arranged in the normally female pose of the left arm bent across the breast and the right arm straight at the side. The mummy had a bent gold sheet vulture crown at its head, and a gold necklace. Apart from Tiye’s name on the shrine, all cartouches had been cut out from the shrine and the coffin. The central figure on the shrine doors had been scratched out, the gold face of the coffin had been torn away. The mummy was declared to be either that of a male, possibly Akhenaten, or his son in law, Smenkhkare. Gaston Maspero, then Director General of Antiquities, described it as “not a tomb, but a secret burying place”, to save the items it contained, and this deposit must be dated to the reign of either Tutankhamun or Ay.

Gold mummy bands, with Akhenaten’s name on them, had been found with the mummy and recorded in the catalog published in 1910, they are also visible in the excavation photographs, but these bands were stolen before reaching the museum in Cairo and have not resurfaced.

The excavation has been dubbed as the worst piece of excavation on record in the Valley. “A notably mismanaged operation from the start… the inadequacy of the work compounded by a very indifferent publication… it is not surprising that material from the tomb passed into the hands of the luxor dealers.” (Harry James, 1992) The canopic jars have been assigned in turns to Tiye, Tutankhamun, Akhenaten, Smenkhkare, and Kiya. The coffin has been understood as originally for Tiye, for Akhenaten, for Smenkhkare before he became king, for a princess (one of Akhenaten’s daughters), for Meryetaten, and again for Kiya. It was then adapted for use by Smenkhkare, or Akhenaten. Modern scholars class the coffin and jars as originally Kiya’s and then adapted for a man, most commonly taken to be Smenkhkare. The main reason for all of this confusion is attributed to the mishandling of the delicate gold bands on the coffin, with their overlaid emendations. The mummy, which is in fact the most examined mummy in Egyptian history, was preliminarily stated as that of a female, because of its pose, yet it has been regarded since as that of a male. Its age is usually given in the lower twenties. That would rule out Akhenaten, and so the majority of the scholars have accepted the mummy as that of Smenkhkare, although recent DNA work and associated anatomical examinations have attempted to revive claims for Akhenaten.

Beyond the arguments over contents, the history of KV55 (as essentially a crime scene) is still a puzzle. When was the tomb last opened and closed in ancient times? And what was the purpose of these reopenings?

In all catalogs and lists of KV55 contents, there is no mention of the strange objects at the Egyptian museum in 2017. And the photographs do not date or look like the excavation images published in 1910 by Davis. Are these the mishandled and misplaced gold mummy bands? Were they reburied and rediscovered in recent times? Are these images an attempt to cover up the disappearance of the bands and stage their reappearance?

Semenkh-Ka Re

Smenkhkare (the customary spelling), came into prominence in the last five years of Akhenaten’s reign, coinciding with the disappearance of Nefertiti. A pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty who ruled for one year, Smenkhkare is virtually unknown and little about him is agreed upon. Sometimes has been described as Akhenaton’s co-regent, lover, and as a nickname assumed by Nefertiti. Today, Smenkhkare’s face, real name (Smenkhkare is an epithet), and age, are subject to debate. Scholars agree however that he was Akhenaten’s son in law, married to princess Meryetaten, and that he ruled for only one year. The historical record of Akhenaten, Smenkhkare and the Amarna period itself was systematically erased by subsequent dynasties, and KV55 might be an instance of these erasures.isDoa Ah